Fourier Optics: Refraction by Snell’s Law

Published:

When light interfaces from one media to another, its phase fronts (lines of constant phase) must stay continuous across the interface of the boundaries. This is true of all physical waves. From this fact, we actually derive Snell’s equation.

Deriving Snell’s Law from Phase Continuity

When a monochromatic plane wave encounters an interface between two dielectric media (with refractive indices $n_1$ and $n_2$), the wave must adapt its direction according to physical constraints. One of the most fundamental of these is*phase continuity: the wavefronts (surfaces of constant phase) must align at the boundary to avoid discontinuities in the field. This requirement gives rise to Snell’s Law.

Phase Fronts and Wave Vectors

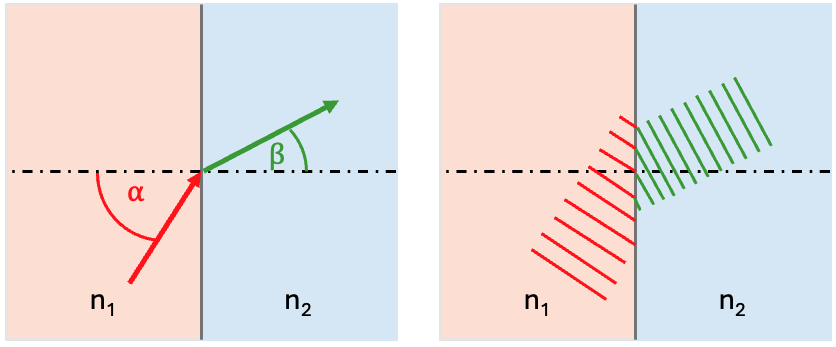

In the figure above, red and green lines represent the phase fronts of the wave in each medium. The wave propagates from medium 1 (left) into medium 2 (right), and the angle of incidence $\alpha$ and the angle of transmission $\beta$ are measured from the surface normal.

Each wavefront is perpendicular to its respective wavevector. The wavevector $\vec{k}$ satisfies:

\[|\vec{k}_i| = \frac{2\pi n_1}{\lambda_0}, \quad |\vec{k}_t| = \frac{2\pi n_2}{\lambda_0}\]where $\lambda_0$ is the wavelength in vacuum. The tangential (in-plane) component of the wavevector must be conserved across the boundary:

\[k_{i,\parallel} = k_{t,\parallel}\]This condition arises from the boundary condition on the electric field derived from Maxwell’s equations, specifically the requirement that the tangential component of the electric field $\vec{E}_\parallel$ must be continuous at the interface.

Tangential Wavevector Continuity

We can express the tangential components of the incident and transmitted wavevectors as:

\[k_{i,\parallel} = |\vec{k}_i| \sin \alpha = \frac{2\pi n_1}{\lambda_0} \sin \alpha\] \[k_{t,\parallel} = |\vec{k}_t| \sin \beta = \frac{2\pi n_2}{\lambda_0} \sin \beta\]Setting these equal yields the Snell’s Law:

\[n_1 \sin \alpha = n_2 \sin \beta\]Refractive Index

The refractive index $n$ of a medium is a dimensionless number that describes how fast light travels through that medium compared to the speed of light in a vacuum. It is defined as $n = \frac{c}{v}$ where $c$ is the speed of light in a vacuum (approximately $2.998 \times 10^8 m/s$) and $v$ is the phase velocity of light in a material. Therefore, to say a material has an index of refraction of $1.2$ basically states that “this material travels 16.7% slower in this material than in a vacuum.” Some common refractive indices are air ($n=1.0003$), water ($n=1.33$), glass ($n=1.4-1.7$), diamond ($n=2.42$), and silicon ($3.5-4.0$).

Recall this relationship $v=f\lambda$ where $v$ is the phase velocity, $f$ is the frequency, and $\lambda$ is the wavelength. The frequency of a wave remains constant since it’s determined by the source wave, so to compensate the velocity must change across the interface. From this, one sees that $v \propto \lambda$. Therefore, the bigger (faster) the velocity is, the bigger (longer) the wavelength is. Alternatively, the smaller (slower) the velocity is, the smaller (shorter) the wavelength is.

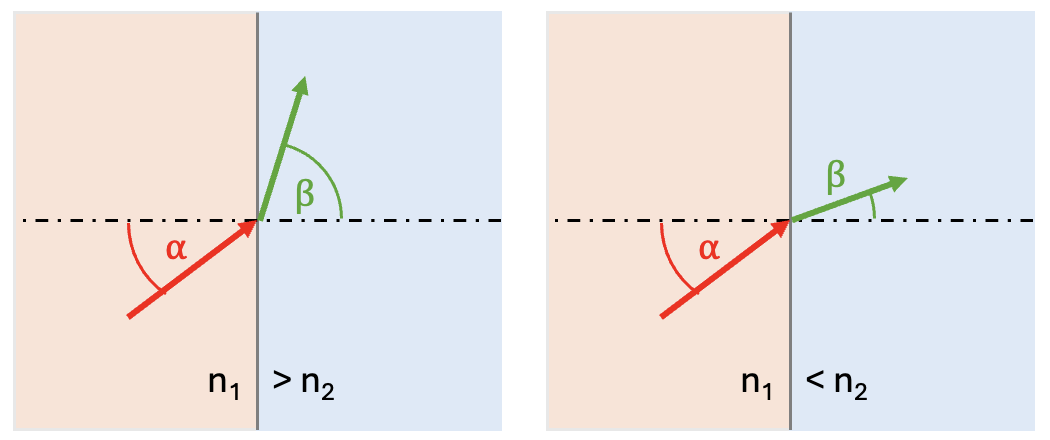

This relationship directly impacts how the wave bends at an interface. If $n_1 > n_2$, then the wave goes into a medium in which it travels faster, so therefore its wavelength is longer. This means that it will bend away from the normal in the second interface. However, if $n_1 < n_2$ then the wave is entering a medium in which it will travel slower and therefore its wavelength will be smaller and it will bend towards the normal.

Also, notice how the phase velocity is dependent on the wavelength, and the refractive index is the speed of light divided by this phase velocity. Therefore, the refractive index is wavelength dependent. This is what is responsible for dispersion, such as when white light producing the many colors of a rainbow as it passes through a prism.

Total Internal Reflection

Notice in snell’s law that there exists an angle $\alpha$ such that $\beta > 1$. In this case, the wave no longer refracts but reflects. This phenomena is called total internal reflection. The angle $\alpha_c$ that produces $\beta= = 90\circ$ where the wave skims the interface is called the critical angle.